The web Browser you are currently using is unsupported, and some features of this site may not work as intended. Please update to a modern browser such as Chrome, Firefox or Edge to experience all features Michigan.gov has to offer.

Woman's Suffrage in Michigan: A Timeline of the Movement

Woman's Suffrage in Michigan: A Timeline of the Movement

A Woman’s Place is Under the Dome:

A timeline detailing some of the most important moments in the fight for woman’s suffrage that occurred in Michigan’s three Capitols.

Woman’s suffrage didn’t happen suddenly in 1920, when the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified. It was a difficult, fraught, and frustrating process that played out in states and state capitol buildings across the country. In Michigan, several generations of women and men devoted over seventy-five years and untold resources to the movement. Along the way, they organized multiple campaigns, celebrated some important incremental victories, and mourned many defeats.

WAYS TO LEARN MORE

Research. Due to the sheer volume of information available in historical state documents, we have been selective in choosing particular moments that we believe to be most important to the fight for woman’s suffrage in Michigan’s Capitols. Anyone interested in learning more is strongly encouraged to check out this bibliography of materials from the Library of Michigan's collections. Some of these items are housed in our Rare Book Room. Please be aware that access to the Rare Book Room is by appointment; to schedule call 517-335-1477 or email librarian@michigan.gov.

Trace Steps. For an even more intimate learning experience, place yourself in the very spaces where many of these events took place. The Michigan State Capitol will be offering special guided tours celebrating the 2020 Women's Suffrage Centennial. Find details on the Capitol's website.

1835

Michigan declares itself a state and writes its first state constitution, the Constitution of 1835, in its first Capitol building, located in Detroit.

Article 2, Section 1 defines the qualifiers of electors thus:

"In all elections, every white male citizen above the age of twenty-one years, having resided in the state six months next preceding any election, shall be entitled to vote at such election; and every white male inhabitant of the age aforesaid, who may be a resident of this state at the time of the signing of this constitution, shall have the right of voting as aforesaid; but so such citizen or inhabitant shall be entitled to vote, except in the district, county, or township in which he shall reside at the time of the election."

During the 1835 Constitutional Convention there had been some debate about omitting the word “white” from the document. Discussions over this word must be contextualized in relationship to at least two groups of potential voters – African American and Native American men. Michigan has always been home to a sizable Native population, many of whom intermarried with French-speaking Michigan residents and formed the state’s Métis culture. Surviving records do not suggest that woman’s suffrage was ever discussed or considered during the proceedings.

Source:

“Constitution of Michigan of 1835.” www.legislature.mi.gov. Michigan Legislature. Accessed January 27, 2020. http://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/historical/miconstitution1835.htm.

1841

A resolution was introduced in the House of Representatives to amend the Constitution of 1835 to extend the vote to “every colored male citizen of the United States, of the age aforesaid, who shall be the owner of a freehold property of the value of two hundred and fifty dollars, and who shall have resided in this state one year, next preceding the election.”

This resolution ultimately did not pass. It serves as an important reminder, however, that additional restrictions were frequently proposed when bodies considered granting the right of suffrage to a previously disenfranchised group of people.

Source:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan of the Annual Session of the Legislature for 1841, pp.444-445. Detroit, MI: George Dawson, State Printer, 1841.

1844

Woman’s suffrage was one of many female-centric issues that reformers sought to change in the mid-19th century. In 1844, the Michigan Legislature broke new ground when it passed “An Act to Define and Protect the Rights of Married Women.” This law granted women the ability to retain any property (including both real estate and personal items such as household goods and clothing) that they had owned before they married. Prior to the passage of this act, women ceased to be able to lay claim to anything she brought to a marriage, including her own clothes. They all become the property of her husband.

In addition, she was also entitled to any property that she received “by inheritance, gift, grant or devise, and the rents, issues, profits and income thereof . . . and none of said property shall be liable for her husband’s debts or engagements.”

Similar, slightly stronger, protections would be enshrined in the Article 16, Section 5 of the Constitution of Michigan of 1850.

Source:

Acts of the Legislature of the State of Michigan Passed at the Annual Sessions of 1844. Detroit, MI: Bagg & Harmon, Printers to the State, 1844, pp. 77-78.

1846

In 1846 Woman’s Rights lecturer Ernestine Rose addressed gatherings in the Hall of the House of Representatives in the first Michigan State Capitol. On Tuesday, March 24, she spoke about “The Science of Government,” and on Thursday, March 26, she focused on “The Antagonistical Principles of Society.” Both addresses were made in the evening, after the actual House session had recessed for the day. Custom suggest that the speeches were probably attended by some members of the legislature, other state officials, and members of the public.

While the exact texts of Rose’s speeches do not survive, it is highly likely that at least one, if not both, of her speeches called for woman’s suffrage among other reforms. She frequently addressed and advocated for a number of ideas considered by many to be radical, including the socialism, freethinking (her preferred term for atheism), the complete abolition of slavery, and the equality of the sexes.

Source:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan, 1846. Detroit, MI: Bagg & Harmon, Printers to the State, 1846, pp. 342, 353.

1849

Only one year after the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman’s Rights Convention a special Senate Committee was tasked with making recommendations for a general revision of the state constitution. The committee responded with a lengthy report in which they went so far as to recommend universal suffrage based on the importance of natural rights and equality, and the deeply-held American belief that government must derive its power from the consent of the governed – including women.

Source:

“Report of the Special Committee on the Part of the Senate, on the General Revision of the Constitution of the State of Michigan.” In Documents Accompanying the Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan at the Annual Session of 1849. Lansing, MI: Munger & Pattison, Printers to the State, 1849, pp. 32-69.

1850

Convention delegates met in the second Michigan State Capitol (located in Lansing) in 1850 to draft a new state constitution. Not surprisingly, debates over extending the franchise to women, black men, Native men, and recent immigrants ensued. The final document granted the vote to male Native Americans who were at least twenty-one years old and did not belong to any tribe.

Source:

“Constitution of Michigan of 1850.” www.legislature.mi.gov. Michigan Legislature. Accessed January 27, 2020. https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/historical/miconstitution1850.htm

1855

By 1855, Michigan women were actively signing petitions asking for the right to vote. Some couched their request in respectful and somewhat timid language, while others preferred to be blunt. From this point forward, Michigan women would submit petitions asking for – or occasionally demanding – the vote at nearly every biennial legislative session thereafter. Some of these petitions were referred to legislative committees for discussion, while others simply languished.

Source:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan. Lansing, MI: Hosmer & Fitch, Printers to the State, 1855.

1867

The Michigan House and Senate voted to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in January of 1867. This Amendment defined citizenship, and, much to the chagrin of many woman’s suffrage supporters, introduced the word “male” into the document.

Sources:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1867. Lansing, MI: John A. Kerr & Co, Printers to the State, 1867, pp. 180-182.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1867. Lansing, MI: John A. Kerr & Co. Printers to the State, 1867, pp. 181-182.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1867, a constitutional convention met in the wooden Capitol for the purpose of writing a third state constitution. Convention delegates received numerous woman’s suffrage petitions, but ultimately voted down removing the word “male” from the constitution 23 to 46. They also rejected by a slimmer margin of 31 to 34 the idea of submitting the question to the voters in a separate proposal.

The document drafted did extend the franchise to African American men. This reform did not come to pass, however, as Michigan voters soundly rejected the document due, in part, to this issue. Black men in Michigan would have to wait three more years to receive their voting rights, until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in February of 1870.

Source:

Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Michigan Convened at the City of Lansing, May 15th, 1867. Vol. II. Lansing, MI: John A. Kerr & Co., Printers to the State, 1867, pp. 775, 791.

1869

On March 31, 1869, Harriet Tenney was confirmed as Michigan’s new State Librarian. This made her the first female state officer (the 19th century equivalent of a department director) in the Peninsular State, and only the third female state librarian nationally. Though Tenney never publicly expressed her opinion on suffrage, her appointment was celebrated as a victory for women and “an entering wedge for suffrage and female office-holding.”

Source:

“An Entering Wedge.” Detroit Advertiser and Tribune, April 9, 1869.

1871

Though delegates to the 1867 constitutional convention ultimately did not vote to enfranchise Michigan women, there was a growing sense that perhaps the time had come. In January 1870, a group of reformers founded the Michigan State Woman Suffrage Association (also known as MSWSA) in Battle Creek. Soon this group was actively lobbying the Legislature for a constitutional amendment enfranchising women, or an acknowledgement that women, as citizens, could now vote under the newly amended U.S. Constitution.

The leaders of MSWSA clearly understood the importance of taking their message to the Capitol. In March 1871, the group held their annual convention in Lansing, timed to coincide with the busy biennial legislative session. In the days leading up to it, a Joint Resolution was introduced “submitting an amendment to the constitution, providing for female suffrage” which was read and referred to committees in both the House and Senate.

While the House ultimately failed to act on this resolution, they granted permission to use their Chamber in the evenings to multiple women who wished to speak on the suffrage issue. First, on Wednesday, March 1, Mrs. Dr. Wheaton of Kalamazoo spoke opposing woman’s suffrage at the same time that Susan B. Anthony was opening the MSWSA conference at Mead’s Hall in downtown Lansing. A trio of pro-suffrage advocates, comprised of Anthony, Judge Livermore, and Mrs. Adele Hazlett, spoke in the House the following night, the latter specifically rebutting Mrs. Wheaton’s arguments. According to the local Lansing State Republican, a pro-suffrage newspaper, both the anti and pro speeches were well attended.

On Friday, March 3, MSWSA sent a resolution to the legislature stating that “We, the members of the Michigan State Woman Suffrage Association . . . request your honorable body to pass a joint resolution to the effect that in your opinion the Legislature of Michigan, in ratifying the 14th and 15th amendments to the federal constitution, annulled all laws of the State denying or abridging the right of the women to vote.” The resolution was signed by Mrs. Mary T. Lathrop, MSWSA President, who proceeded to address both the House and the Senate in their respective Capitol Chambers. This was an extraordinary moment for the women of Michigan, who were now personally advocating for suffrage in the very rooms where the laws of Michigan were made. Yet even this direct petition failed to change the minds of the male legislature.

Source:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1871. Vol. II. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co, Printers to the State, 1871, pp. 882, 945, 1022, 1104-1105.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1871. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co., Printers to the State, 1871, pp. 809-810.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. History of Woman Suffrage. Reprinted. Vol. III. New York, NY: Source Book Press, 1970, pp. 515-516.

“Woman's Suffrage Convention.” Lansing State Republican, March 2, 1871.

“State Woman’s Suffrage Association” Lansing State Republican, March 9, 1871.

1874

In the fall of 1873 a special Constitutional Commission of eighteen gubernatorial appointees met in Lansing to discuss and propose amendments to the 1850 Constitution. While they did not endorse including woman’s suffrage, their recommendations went to the Legislature, who had a different opinion. On March 12, 1874, during a special spring session, the Michigan State Woman Suffrage Association sent a memorial to the Legislature asking that they strike out the word “male” from the state constitution. “Women are also governed,” the association argued, “while they have no direct voice in the government, and made subject to laws affecting their property, their personal rights and liberty, in whose enactment they have had no voice.” By righting this wrong the Legislature would “elevate the entire people to the highest practicable place of intelligence and true civilization.”

Both the House and Senate took heed and voted to submit a constitutional amendment enfranchising women to the voters via a separate one-issue ballot marked “Woman suffrage – Yes” or “Woman suffrage – No” at the 1874 election.

Excited about the potential of this amendment, MSWSA reconvened in Lansing on May 6 and 7. This time, the group met in Representatives Hall, in the Capitol itself. Over the course of two days, approximately 300 men and women heard a lecture by Elizabeth Cady Stanton; read congratulatory letters from other state and national suffrage leaders; and began organizing a multi-tiered campaign consisting of state, county, and township level suffrage associations. These associations would recruit and host competent lecturers, print and distribute documents, frame convincing arguments and conclusions, and fundraise for the cause. In addition, following the protocol of the time, the MSWSA would need to furnish ballots for every polling place, as actual units of government did not yet print their own.

In the months that followed, local suffrage advocates continued to meet in the wooden Capitol, which had long served Lansing as a sort of unofficial town hall. Towards the end of October, the Ingham county chapter of the Friends of Impartial Suffrage met with other likeminded area groups back in Representatives Hall. Together they reaffirmed their campaign work and resolved to encourage the formation of “a committee of five or more ladies be appointed in each township or ward to present the question of Woman Suffrage at the polls at the coming election.”

Despite the best efforts of both local and state level volunteers, the proposed amendment to the constitution failed dramatically, with 40,077 yes votes and 135,957 no votes.

Source:

The Constitution of Michigan with Amendments Thereto as Recommended by the Constitutional Commission of 1873. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1873.

Fairlie, John A. “The Referendum and Initiative in Michigan.” In The Initiative, Referendum and Recall, p. 156. Philadelphia, PA: American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1912.

Jenison Woman’s Suffrage Scrapbook, Rare Book Room, the Library of Michigan, an agency of the Michigan Department of Education.

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan Extra Session 1874. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1874, pp. 94, 172-174.

Journal of the Michigan Senate of the State of Michigan Extra Session 1874. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1874, pp. 128-129.

Proceedings of the Michigan State Woman-Suffrage Association at Its Fifth Annual Meeting. Kalamazoo, MI: Daily Telegraph Book and Job Printing House, 1874.

1875

On March 29, 1875, J.N. Potter of Romeo, Michigan, deposited an item known affectionately as “The Pendell Watch” in the State Library, which also acted as a museum for important Michigan objects and relics. The watch had been donated to the suffrage cause by Mrs. Pendell of Battle Creek during the 1874 MSWSA meeting in Lansing. Throughout the course of the 1874 campaign, Mrs. M. Adele Hazlett, a popular suffrage speaker, repeatedly “sold” the watch at her lectures to raise money for the cause. It remained on exhibit in the Capitol for many years.

Source:

“The Pendell Watch.” Lansing Republican, March 30, 1875.

1881

The Michigan Legislature took a tiny step towards enfranchising women when, in 1881, they passed a new law that permitted every person (twenty-one years of age and over) who paid school taxes in a district to vote on all school related questions at school meetings. In addition, parents and legal guardians of school age children who were on the local school census could vote during school meetings on questions that did not involve raising monies via taxes. This extremely limited gain was a reminder that, by the late 19th century, the education of children fell into the so-called “feminine sphere.” Moral mothers were encouraged to extend their reforming influence to the schools in order to improve their children’s educational prospects.

Source:

Public Acts and Joint and Concurrent Resolutions of The Legislature of the State of Michigan Passed at the Regular Session of 1881. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1881, p. 168.

1885

After organizing in Flint in May of 1884, the new Michigan Equal Suffrage Association (or MESA) sent a petition to the Legislature asking for municipal suffrage. Their argument was based, in part, on the fact that the Legislature had already granted women the vote at school meetings.

“If municipal suffrage to women would be unconstitutional, then is the law allowing them to vote at school meetings unconstitutional. That is a part of municipal suffrage, and quite as important a part as that of voting at town meetings.

“Once admit that the Legislature has power to grant suffrage at all in municipal affairs, to women, and you admit that they have the power to grant in full. And this is admitted in the act giving them municipal suffrage at school meetings.

“The power you undoubtedly have, and in giving them a vote at school meetings you admit that you have it, and you must find some other pretext for the refusal, or admit you are wrong if you defeat the measure.”

MESA clearly saw municipal suffrage as the next step in the march towards full female enfranchisement. So did the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), whose State Superintendent of Franchise sent a memorial to the Legislature a few days after MESA. Soon dozens of supportive petitions poured in to the Capitol from numerous counties.

Sources:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1885. Vol. I. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1885, pp. 374-376.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1885. Lansing, MI: W.S. George & Co., State Printers & Binders, 1885, pp. 172-175.

1887

The Michigan Equal Suffrage Association met at the Capitol for its third annual convention on January 13 and 14 in 1887. They convened on the fourth floor in the rooms used by the Michigan Pioneer Society while the Legislature met in their chambers two floors down. Mrs. Mary Doe, the President of MESA, was no doubt familiar with these spaces, as in the mid-1880s she was working in the Capitol as an extra clerk in the Secretary of State’s Office. Mrs. Doe had also presided at an organizational meeting of local Lansing area suffragists in the Pioneer Rooms the previous March.

MESA hosted two of the nation’s most prominent suffrage advocates at the 1887 conference - Rev. Anna Howard Shaw and Susan B. Anthony. They were both granted the use of the House Chamber where they spoke on January 13 and 14th, respectively.

For Shaw, the event must have seemed like a homecoming of sorts, as she had spent much of her youth in rural Michigan. She pursued her education at the high school in Big Rapids and then Albion College before leaving the state to attend Boston University’s divinity school. Shaw eventually received both her license to preach in the Methodist Protestant Church and then her M.D. from Boston University in 1886.

Sources:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1887. Vol. I. Lansing, MI: Thorp and Godfrey, State Printers and Binders, 1887, p. 20.

“Programme of the Third Annual Convention of the Michigan Equal Suffrage Association,” 1887. Rare Book Room, The Library of Michigan, an agency of the Michigan Department of Education.

1889

In March of 1889, MESA returned to the Capitol’s Pioneer Rooms for their annual conference. According to a report in the Detroit Free Press, about forty women attended. Among the matters they discussed was “the question of the constitutionality of the new law permitting Detroit ladies to vote for school inspectors.” In an interesting gender role reversal, one of the female attendees dared to suggest that the men who would be deciding a pending court case on the matter might be swayed by caprice and irrationality. “Mrs. Eaglesfield made the rather startling assertion that the decision of the Supreme Court on the constitutionality of the two measures would not be based upon the merits of the case, but would depend solely upon what the justices had eaten for breakfast and the condition of their digestion.”

On Thursday, May 16, dozens of MESA members returned to witness a remarkable event in the House Chamber. By a vote of 58 to 34 the House passed a bill that granted women citizens the right to vote in municipal (school, village, and city) elections. According to one newspaper reporter, “Over 100 members of the Michigan Equal Suffrage Association lined Representative Hall and waved their handkerchiefs jubilantly when the bill was passed.”

The Senate, however, proved to be less liberal. The same bill failed on a 10 to 13 vote on the other side of the building.

Sources:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1889. Vol II. Lansing, MI: Darius D. Thorp, State Printer and Binder, 1889, pp. 1616-1617.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1889. Vol. II. Lansing, MI: Darius D. Thorp, State Printer and Binder, 1889, pp. 893-894.

“Woman Suffrage.” Detroit Free Press, March 20, 1889.

“Woman Suffrage in Michigan.” The Weekly Palladium, May 17, 1889.

1891

Suffrage supporters in Michigan resolved to try again during the spring of 1891. Some, like the Crystal Grange No. 411, continued to ask for full suffrage. On February 10 their blunt, matter-of-fact petition was read into the House Journal.

“WHEREAS, Women are human beings, and as a rule are just as intelligent, and are just as much interested in the welfare of the nation as men, and should there be allowed the free use of the ballot; therefore

“Be it resolved, By Crystal Grange that our Senator and Representative at Lansing be instructed to use their influence to so amend the State constitution of Michigan as to give women the right of suffrage with no limitations except such as apply also to men.”

Many women, however, were not bold enough to ask for full suffrage. Some preferred to petition only for municipal suffrage, advocating for it under the guise of “municipal housekeeping.” While some still felt that women should be barred from state and national politics, local matters were different. Women, as the keepers of morality and virtue, could and should use their positions to advocate for a series of progressive reforms, including better education, healthcare, and sanitation.

Along the way, they carefully and tactfully raised awareness about several decidedly complicated issues. Some advocated for increased job opportunities for women, thereby hoping to decrease the number of girls and women forced into prostitution. They lobbied the state to build a separate reform school for girls and made sure that women were hired to staff it, so as to avoid potential misconduct and exploitation. Many labored long and hard to limit access to alcohol, all too aware that substance abuse promulgated hunger, abuse, and could kill. Some bold women even signed their names on petitions to raise the age of consent or lengthen the sentences of criminals convicted of rape.

These women had convictions. Many of them believed that, as women, it was their God-given duty to protect their families and shield their homes and communities from an increasingly licentious and sinful culture. They prayed, volunteered, worked, and donated money and endless hours to important and sometimes controversial causes.

They also used their voices in the Capitol, where they continued to petition and lobby elected officials on a number of issues. House and Senate Legislative Journals from this period include an increasing number of requests and demands from women clearly frustrated by the lack of legal protections for women and children.

In February of 1891, women who supported municipal suffrage and were active members of the WCTU advocated at hearings held in Representatives Hall during the regular MESA convention. But the votes still were not there. In May the Senate defeated another municipal suffrage bill by one excruciating vote, 15 to 14.

Sources:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1891. Vol. I. Lansing, MI: Robert Smith & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1891, p. 292.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1891. Vol. II. Lansing, MI: Robert Smith & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1891, pp. 994-995.

“The Legislature.” Detroit Free Press, May 14, 1891.

“The Seventh Annual Convention.” Detroit Free Press, February 11, 1891.

1893

MESA returned to the Capitol for yet another convention in early February of 1893. This time, Rev. Caroline Bartlett Crane and Rev. Anna Howard Shaw spoke in the Senate Chamber. Presumably the women chose this chamber, the smaller of the two, in acknowledgement that the Senate had been the biggest stumbling block in the state legislative process thus far.

The tide finally began to turn later that spring. Once again, a bill was introduced that granted municipal suffrage to Michigan women. This time, however, it came with a serious caveat. Only “women who are able to read the constitution of the State of Michigan, printed in the English language” would gain the vote under the new proposal. Any interested woman would have to prove her fluency and literacy by reading at least one section of the constitution before the board of registration. Based on her ability, the board could then either proceed with her registration, or disqualify her.

Governor Rich signed the bill on May 27, 1893. Not long after, he received a telegraph from Susan B. Anthony (President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association) and Emily Ketchum (President of MESA), who were both in Chicago, extending their gratitude to him for the “culminating act of your official life . . .”

The celebration did not last long, however. Soon the legality of the new act came into question. A mandamus ruling was requested from the Michigan Supreme Court regarding carrying out the provisions of the act. On October 24 the Court ruled (Justice McGrath writing) that the state constitution did not give the Legislature the ability to create a new class of voters. Thus, women could not cast ballots in municipal elections. The next day, a Livingston County newspaper announced the decision with the headline “Women Must Weep.”

(In an interesting twist the Attorney General issued a ruling not long after saying that women who had been voting at school meetings, under the law passed in 1881, could continue to do so.)

Sources:

Coffin v Bd of Election Comm’rs of Detroit, 97 Mich. 188; 56 N.W. 567 (1893)

Gov. Rich Commended.” Detroit Free Press. June 1, 1893.

Public Acts and Joint and Concurrent Resolutions of the Legislature of the State of Michigan Passed at the Regular Session of 1893. Lansing, MI: Robert Smith & Co, State Printers and Binders, 1893, pp. 225-226.

Report of the Attorney General of the State of Michigan for the Year Ending June 30, A.D. 1894. Lansing, MI: Robert Smith & Co., State Printers and Binders, 1893, pp. 150-151.

“Women Must Weep.” The Livingston Democrat. October 25, 1893.

1908

In the spring of 1906 the men of Michigan voted to call a constitutional convention commencing in 1907. The announcement reignited hope among state suffrage advocates who began to ready their arguments and make travel plans.

By this time, woman’s suffrage had become politically and socially tied to the prohibition of alcohol. Some state and national leaders were wary that this close association might push away male delegates and voters who did not support the reform. However, when it came time to lobby the convention, MESA’s leadership put aside their doubts and joined forces with a number of organizations hoping that a united show of force would carry the day.

On January 8, 1908, men and women representing the State Grange, the Maccabees, the Detroit Garment Workers, the State Woman’s Press Association, the Michigan Federation of Labor, the WCTU, MESA, and several women’s clubs gathered to make their case to the Committee on Elections and Elective Franchise. The hearing took place in Representatives Hall and was attended by many delegates and even Governor Fred Warner.

Suffrage supporters opened by noting that they had been told for years that when the women of Michigan were ready to ask for the ballot, the men of Michigan would give it to them. And ask they did. A total of ten sperate speakers, each representing her own organization, argued that women didn’t just want the ballot. They needed the ballot. And their communities, and their state, needed them to have it.

After these presentations NAWSA President Rev. Anna Howard Shaw and Mrs. Catherine Waugh McCulloch of Chicago spoke. McCulloch chronicled the wrong done to Michigan women under the 1850 Constitution. The world had changed over the last 58 years, she argued. When the 1850 Constitution was adopted, “You had then no women ministers, no women doctors or dentists or lawyers, such as your university now sends forth; no women notaries, or country school commissioners or school inspectors, or bankers or brokers; quite likely, no woman principal of a school, probably no high school graduates, few women teachers, no woman bookkeeper, stenographer, clerk, perhaps no woman in store, office or factory, no women in clubs. The men of fifty-eight years ago would be amazed if they could return to earth and discover the wonderful advance made by women,” she declared.

Yet Michigan women, many of whom were now well-educated, who had worked at one time or another, and who labored on behalf of their communities through clubs and volunteer organizations, were unfairly restricted by antiquated laws. “Fifty-eight years of constitutional humiliation has been sufficient to make intelligent women appreciate being now placed by you on a legal and political equality with men,” McCulloch stated.

The committee hearing ended auspiciously with many congratulations and good wishes. The provision was reported favorably, and sent to the full delegation, who debated the issue in the same room on January 29, 1908. A MESA member later wrote, “Friendly members of the convention spoke earnestly and well, and to the credit of Michigan men be it said not a voice was raised in opposition. But the potent vote told the old tale, and stood 38 in favor to 57 against.”

Some delegates claimed that they failed to vote for the proposal out of fear that it would doom the fate of the entire new constitution, perhaps thinking of 1867. Others suggested that the issue should have been submitted to the voters separately. In the end, the new constitution, which was adopted by male voters in 1908, only granted women who paid taxes the right to vote on local bonding issues, or on questions involving the direct expenditure of public monies. It was something – but not enough.

Sources:

McCulloch, Catharine Waugh. “Some Wrongs of Michigan Women 1850-1908.” Michigan Constitutional Convention, January 29, 1908.

“Proposition to Call a Constitutional Convention.” Detroit Free Press, April 21, 1906.

“Report of the Twenty-fourth Annual Convention of the Michigan Equal Suffrage Association, Rare Book Room, the Library of Michigan, an agency of the Michigan Department of Education.

1911

Determined to press on despite their many defeats, MESA returned to the Capitol again for the 1911 session. They were met with continued resistance in the Legislature, where a resolution to amend the constitution failed to be taken up in the Senate and was not passed in the House.

The House did agree to let English suffragist Sylvia Pankhurst speak in Representatives Hall on the afternoon of March 24. The daughter of longtime militant suffrage activist Emmaline Pankhurst, Sylvia had already been jailed in England multiple times for the cause, despite being only nineteen years old.

The tone used by the local Lansing media reveals much about the challenges the suffrage movement continued to face in the Capitol. “A call of the house prevented the legislators from escaping even had they desired to get away,” a reporter wrote, “but inasmuch as the address was really interesting and delivered in an excellent manner it was well worth hearing.

“All of the men employes [sic] in the capitol building were excused from work for an hour in order that they might hear Miss. Pankhurst.”

Another news story, published a day later, was subtitled “Not Very Warlike.” The article began with “Not at all militant in appearance and less so in the character of her talk, Miss Sylvia Pankhurst . . . surprised and delighted the members of the legislature Friday afternoon when she addressed them. Miss Pankhurst’s talk was one of the sanest and best arguments that has yet been advanced in favor of the cause and could a vote on the suffrage bill have been taken after her speech it is quite likely the bill would have found many more supporters than it had when it was up for passage some weeks ago.” Such statements were easy to make, of course, after the suffrage bill was safely dead for another session. One also can’t help but wonder how Michigan suffragists who had been sanely, articulately arguing for the cause for years, felt upon reading the coverage.

Sources:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1911. Vol. I. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1911.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1911. Vol. II. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1911.

“Miss Pankhurst Talks in Lansing.” The State Journal, March 24, 1911.

“Suffraget [sic] Wins Friends By Talk.” The State Journal, March 25, 1911.

1912

Governor Chase Osborn reignited the suffrage conversation when he called a special Legislative session in February of 1912. He specifically authorized and requested that the House and Senate consider an amendment to the constitution “providing for giving and insuring the right of [full] suffrage to the women of Michigan.” No chief executive had ever taken this bold of a stance on the issue. By sending this message during a special session, Osborn was telling the Legislature that they were required to consider the matter.

The Legislature, however, wasn’t in the mood to follow orders. The House introduced a concurrent resolution which was printed and sent to committee, where it languished. The Senate drafted a different concurrent resolution which was voted down on March 14. Six days later, on March 20, the Legislature adjourned and attempted to go home.

Osborn had other ideas. As soon as the gavel dropped he promptly called a second special session, to commence immediately. This time he changed the wording slightly and told the Legislature that they had to “consider legislation by and through which the question of amendment to the constitution shall be submitted to the electors of Michigan providing for giving and insuring the right of suffrage to the women of Michigan.”

It didn’t take long for advocates on both sides of the issue to make their voices heard. Dr. A. S. Warthin, who was involved in anti-tuberculosis efforts, urged the Legislature to put a constitutional amendment for woman’s suffrage on the ballot. “. . . I have become convinced that we can never accomplish anything in improving health conditions in the state of Michigan until women can vote,” he wrote. In contrast, the Knights of the Royal Ark of Wayne County, a cadre of saloon keepers, sent letters to each Legislator stating they were “. . . unanimously opposed to any liquor legislation or any change in the present bonding law and women suffrage . . .” This sparked the ire of the Governor, who warned the lawmakers against the “saloon and brewery interests.”

Meanwhile, suffrage supporters were swarming the Capitol, simultaneously thrilled and nervous about the sudden flurry of action. They initially focused their efforts on Senate members, who voted 23 to 5 on March 26 to pass Senate Concurrent Resolution No. 3, which called for a statewide vote on full female suffrage during the November presidential election. The House followed suit on March 28 with what the jubilant Michigan Equal Suffrage Association deemed a “landslide” 75 to 19 vote.

Over the next several months, a number of woman’s organizations campaigned hard for the amendment. Their most significant opposition came, not surprisingly, from the liquor lobby, which believed that female suffrage would bring prohibition. Ultimately, the amendment failed to pass by less than a thousand votes. While accusations of voter fraud and mismanagement made headlines for several days, no legal action resulted from the disappointing election.

Sources:

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan First Extra Session February 26 to March 20, 1912. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1912, pp. 81, 87.

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan Second Extra Session March 20 to April 10, 1912, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1912, pp. 15, 18-19, 34-36, 83-85.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan First Extra Session February 26 to March 20, 1912. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1912, pp. 77, 128-129.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan Second Extra Session March 20 to April 10, 1912. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1912, pp. 13, 41-43, 97.

1913

After their narrow loss in the 1912 election, suffrage supporters wasted no time in reaching out to the Legislature and asking for a second vote on a constitutional amendment. A joint hearing in the Capitol on February 5, 1913, drew both suffrage supporters and one out-of-state anti- suffrage speaker. The Legislature put the matter on the spring ballot, but it failed badly due to low voter turnout and an increasingly active anti-suffrage movement (largely funded by the alcohol lobby).

Sources:

“Year Book of the Michigan Equal Suffrage Association and Report of the 28th Annual Convention Jackson, Michigan, Nov. 5, 6, 7, 1913." Rare Book Room, The Library of Michigan, an agency of the Michigan Department of Education.

1915

In the fall of 1915, the Capitol played host to the State Federation of Women’s Clubs’ Convention. The event drew leading women from across the State who discussed and passed resolutions on issues including dress reform, home economics, and public health. Meetings and events were held in Representatives Hall, the Senate Chamber, and even the Executive Parlor, where Gov. and Mrs. Ferris hosted an elegant reception. On the final day of the conference, the Federation voted unanimously to endorse prohibition, woman’s suffrage, and to ask Congress to pass the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, guaranteeing the right to vote to women across the United States

Sources:

“Board Session Opens Women's Clubs' Meeting.” The State Journal. October 19, 1915.

“Women Indorse Prohibition and Equal Suffrage.” The State Journal. October 22, 1915.

“Women Name Same Officers to Serve Again.” The State Journal. October 21, 1915.

“Women's Clubs' President Raps Dresses, Music.” The State Journal. October 20, 1915.

1917

“Women Likely to be Given Ballot,” a headline in Lansing’s local newspaper read on March 13, 1917. “Unless something unforeseen happens a bill giving the women of Michigan the right to vote for presidential electors will be passed by the Michigan legislature, and a constitutional amendment to be submitted at the general election in 1918 providing for universal suffrage will also be ratified,” The State Journal reported.

What had changed? Well, according to the newspaper, the Legislature had come around to realize that suffrage was, like prohibition (which had passed statewide in Michigan in 1916 and went into effect on May 1, 1917), inevitable. It was being adopted in more and more states across the country. It was suddenly the thing to do. Therefore, the Legislature simply decided to “clamber aboard the suffrage bandwagon.”

There were actually two major suffrage reforms working their ways through the Legislature that spring. One bill, authored by Senator Damon of Mt. Pleasant, granted women the right to vote for presidential electors. This bill was passed in the Senate on March 21 by a vote of 22 to 7, and in the House on April 18 with 64 members voting yes, and 30 voting no.

At virtually the same time, the Legislature passed a Joint Resolution placing another proposed constitutional amendment on the ballot in 1918. HJR 14, as it was known initially, passed the House 71 to 21 on March 28. The Senate gave its approval, 26 votes to 4, on April 19.

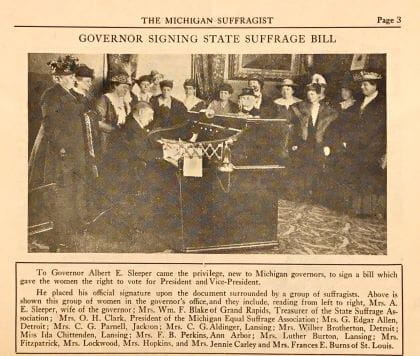

Not surprisingly, the votes were carefully watched by hopeful MESA members, who lobbied hard and “applauded vigorously” from the gallery. Several returned to witness Governor Sleeper signing the presidential elector bill in early May. A photograph of the women, watching intently, ran in the next issue of The Michigan Suffragist, the organization’s newsletter.

Sources:

“Governor Signing State Suffrage Newsletter,” Michigan Suffragist, May 1917, Volume Four, Number Four. Rare Book Room, The Library of Michigan, an agency of the Michigan Department of Education.

Hayes, Gurd M. “Presidential Vote is Given to Women.” The State Journal, April 19, 1917.

Hayes, Gurd M. “Women Likely to Be Given Ballot.” The State Journal. March 13, 1917.

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1917. Vol. I. Lansing, MI: Wynkop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1917, pp. 926-929.

Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan 1917. Vol. II. Lansing, MI: Wynkop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1917, pp. 1507-1510.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1917. Vol. I. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1917, pp. 633-634.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan 1917. Vol. II. Lansing, MI: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1917, pp. 1456-1459.

1918

After the successes of the 1917 session, Michigan suffrage supporters hurried back to their own communities where they spent the next year and a half aggressively campaigning for the cause. The Legislature did not return in 1918, and MESA decided to have their annual convention in Detroit, a logical choice considering that this populous area would be key for winning the election. As a result, the Capitol remained relatively quiet in relation to suffrage, save for individual conversations between the hundreds of men and women then working in the building.

On November 5, voters went to the polls. Early election results looked promising, but after the 1912 situation no one wanted to declare victory too soon only to suffer another heart-breaking defeat. The State Journal reported on November 6 that the amendment had passed in Lansing and signs seemed positive at the county level. A week later the official canvass showed that Ingham County voters supported suffrage with 7,335 yes votes to 5,497 no votes. The measure also carried statewide, finally giving Michigan women a victory nearly three quarters of a century in the making.

Sources:

“Vote Canvass is Made in Ingham.” The State Journal. November 13, 1918.

“Woman Suffrage Gets O.K. In City.” The State Journal. November 6, 1918.

1919

During a special session in June 1919, the Michigan Legislature became, on June 10, the third state in the nation to officially ratify the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which had only been given final Congressional approval a few days earlier on June 4). In a show of overwhelming support, the all-male legislature voted unanimously for its ratification.

“State Ratifies Equal Suffrage” read a front-page headline in The State Journal the next day. “Few women present as measure passes.” In fact, the ratification was taken up in such haste that the only women present in the Chamber to bear witness were a few female House committee clerks, sitting quietly on the divans that bordered the chamber floor. No doubt they were smiling and thinking about who they would be voting for when the Legislature was next up for election in 1920.

Sources:

“State Ratifies Equal Suffrage.” The State Journal. June 11, 1919.

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

(Affectionally known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment)

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Updated 04/02/2024